กิจกรรมหุ่นยนต์เดินตามเส้นอัตโนมัติตามแนวทางสะเต็มศึกษาเพื่อพัฒนาแนวคิด เรื่อง แรงและการเคลื่อนที่

Main Article Content

Abstract

Akapong Buachoom, Thanida Sujarittham, Karntarat Wuttisela, Choksin Tanahoung and Sura Wuttiprom

รับบทความ: 8 มิถุนายน 2564; แก้ไขบทความ: 21 สิงหาคม 2564; ยอมรับตีพิมพ์: 18 กันยายน 2564; ตีพิมพ์ออนไลน์: 27 เมษายน 2565

บทคัดย่อ

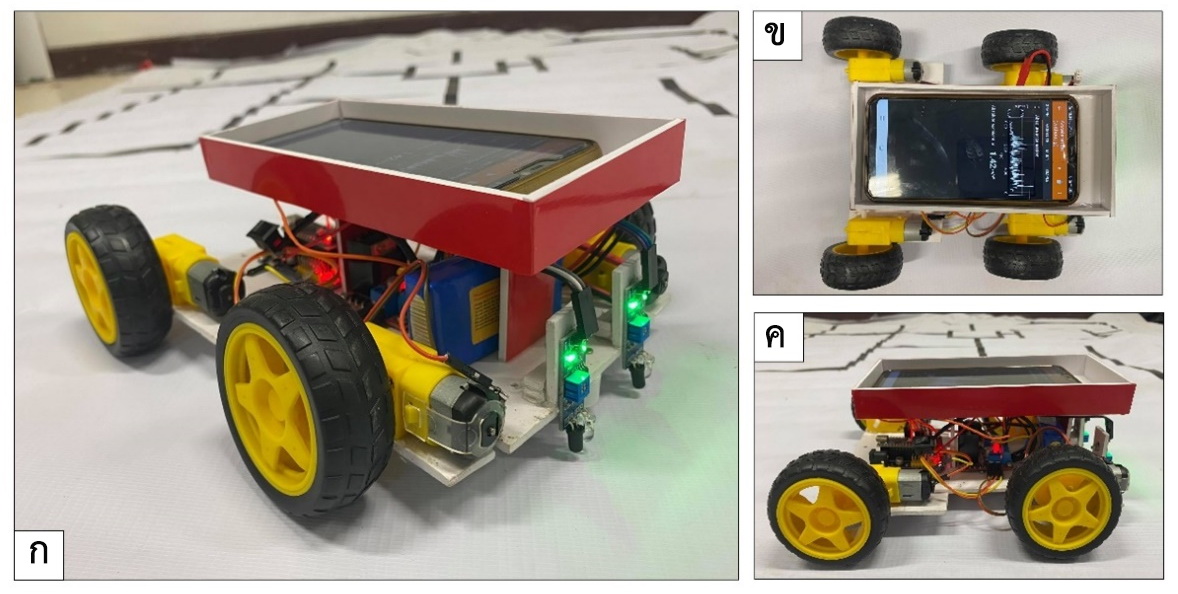

การวิจัยนี้มีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อ 1) สร้างและหาประสิทธิภาพของหุ่นยนต์เดินตามเส้นอัตโนมัติ และ 2) พัฒนาแนวคิด เรื่อง แรงและการเคลื่อนที่ของนักเรียน กลุ่มที่ศึกษาในการวิจัยครั้งนี้คือ นักเรียนชั้นมัธยมศึกษาปีที่ 4 ภาคเรียนที่ 2 ปีการศึกษา 2563 จำนวน 27 คน เครื่องมือในการวิจัยประกอบไปด้วย หุ่นยนต์เดินตามเส้นอัตโนมัติและแบบประเมินแนวคิด เรื่อง แรงและการเคลื่อนที่ (FMCE) การจัดการเรียนรู้ใช้กระบวนการออกแบบเชิงวิศวกรรม 6 ขั้นตอน ดังนี้ ขั้นที่ 1 นักเรียนร่วมกันวิเคราะห์ปัญหาจากสถานการณ์ที่กำหนด จากนั้นกำหนดเงื่อนไขในการออกแบบและสร้างหุ่นยนต์ ขั้นที่ 2 นักเรียนรวบรวมข้อมูลและแนวคิดที่เกี่ยวข้องกับการแก้ปัญหาจากหุ่นยนต์ต้นแบบ จากนั้นออกแบบวงจรเซนเซอร์อินฟราเรดและวงจรควบคุมมอเตอร์ ขั้นที่ 3 นักเรียนนำความรู้จากการรวบรวมข้อมูลมาใช้ออกแบบวงจรไฟฟ้าของหุ่นยนต์และโครงสร้างของหุ่นยนต์ ขั้นที่ 4 นักเรียนสร้างหุ่นยนต์ตามที่ออกแบบไว้ ขั้นที่ 5 นักเรียนทดสอบหุ่นยนต์โดยใช้แอปพลิเคชัน Phyphox วัดความ เร่งของหุ่นยนต์ และขั้นที่ 6 นักเรียนนำเสนอผลงานโดยการแข่งขันหุ่นยนต์ ผลการวิจัยพบว่า หุ่นยนต์เดินตามเส้นอัตโนมัติที่ผู้วิจัยสร้างและพัฒนาขึ้น มีประสิทธิภาพร้อยละ 98.51 จากการประเมินความก้าวหน้าทางการเรียนด้วยวิธีของ Hake มีความก้าวหน้าในความเข้าใจในแนวคิดฟิสิกส์ เรื่อง แรงและการเคลื่อนที่ อยู่ในระดับปานกลางเท่ากับ 0.60

คำสำคัญ: หุ่นยนต์เดินตามเส้นอัตโนมัติ แรงและการเคลื่อนที่ สะเต็มศึกษา

Abstract

The objectives of this research are to 1) design and assess the efficiency of a line-follower robot, and 2) develop concept of force and motion of students. The study involved 27 tenth grade students during the second semester of the 2020 academic year. The research tools consisted of a line-follower robot and force and motion conceptual evaluation (FMCE). The learning activities were followed a 6–step engineering design process. Step 1, students analyze the problem from the given situation. Then set the conditions for designing and building the robot. Step 2, students gather information and ideas related to problem–solving from the prototype robot. Then designed an infrared sensor circuit and a motor control circuit. Step 3, students apply their knowledge from data collection to design robotic circuits and robot structures. Step 4, students build a robot as designed. Step 5, students test the robot using the Phyphox application to measure the robot's acceleration. Step 6, students present their work by the robotics competition. The results showed that the efficiency of a line–follower robot set was 98.51 percent. From Hake’s learning gain method, the student had the medium gain in force and motion concept <g> of 0.60.

Keywords: Line–follower robot, Force and motion, STEM education

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

References

Brown, D. E. (1989). Students’ concept of force: The importance of understanding Newton’s third law. Physics Education 24(6): 353–358.

Buachoom, A., Wuttiprom, S., and Sujarittham, T. (2020). Applying Arduino platform for physics measurement instruments. Journal of Science and Science Education 3(1): 98–104. (in Thai)

Chinmuaeng, S., and Bongkotphet, T. (2019). STEM Approach based on engineering design process on sound for enhance of creativity and innovation of the 11th grade students. Journal of Education Burapha University 31(1): 59–74. (in Thai)

González, M. Á., González, M. Á., Martín, M. E., Llamas, C., Martínez, Ó., Vagas, J., Herguedas, M., and Hernández, C. (2015). Teaching and learning physics with smartphones. Journal of Cases on Information Technology 17(1): 31–50.

Hake, R. (1998). Interactive engagement vs traditional methods: A six–thousand survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics course. American Journal of Physics 61(1): 64–74.

Halloun, I. A., and Hestenes, D. (1985). The initial knowledge state of college physics students. American Journal of Physics 53(11):1043–1048.

Hartigan, C., and Hademenos, G. (2019). Introducing ROAVEE: An Advanced STEM–based project in aquatic robotics. The Physics Teacher 57(1): 17–20.

Hestenes, D., and Wells, M. (1992). A mechanics baseline test. The Physics Teacher 30(3): 159–166.

Kaps, A., Splith, T., and Stallmach, F. (2021). Implementation of smartphone–based experimental exercises for physics courses at universities. Physics Education 56(3): 1–8.

King, D. and English, L. D. (2016). Engineering design in the primary school: Applying STEM concepts to build an optical instrument. International Journal of Science Education 38(18): 2762–2794.

Lertcharoenrit, T., Pimthong, P., Kityakarn, S., Munprom, R., and Ugsokid, S. (2018). The 12th Grade students’ STEM understanding in the topic of PM 2.5. Kasetsart Educational Review 35(3): 176–188. (in Thai)

Phornphisutthimas, S. (2013). Learning management of science in 21st century. Journal of Research Unit on Science, Technology and Environment for Learning 4(1): 55–63. (in Thai)

Smith, T. I., and Wittmann, M. C. (2008). Applying a resources framework to analysis of the Force and Motion Conceptual Evaluation. Physics Education Research 4(2): 1–12.

Staacks, S., Hutz, S., Hütz, H., and Stampfer, C. (2018). Advanced tools for smartphone–based experiments: Phyphox. Physics Education 53(4): 1–8.

The institute for the promotion of teaching science and technology. (2014). Basic knowledge of STEM education. Retrieved from http://www.stemedthailand.org, Oc-tober 1, 2020.

Vartiainen, H., Liljeström, A., and Enkenberg, J. (2012). Design–oriented pedagogy for technology–enhanced learning to cross over the borders between formal and Informal environments. Journal of Universal Computer Science 18(15): 2097–2119.

Vogt, P., and Kuhn, J. (2012). Analyzing free fall with a smartphone acceleration sensor. The Physics Teacher 50(3): 182–183.